|

| I was just thinking we could take of it right here, in Brainerd |

(Part One, Part Two)

Over the course of the past two blog posts, I have been looking at different aspects of Pinker, Nowak and Lee’s (PNL’s) theory of indirect speech, as presented in their article “The Logic of Indirect Speech”. PNL’s goal is to offer some explanation for the prevalence of indirect speech acts in human social discourse.

The motivating reason for doing this is that indirect speech poses something of a paradox. If people do not directly say what they mean — i.e. if they try to implicate what they mean — they adopt a form of locution that is inefficient and runs the risk of being misunderstood. So why bother? Why not just say what you really mean?

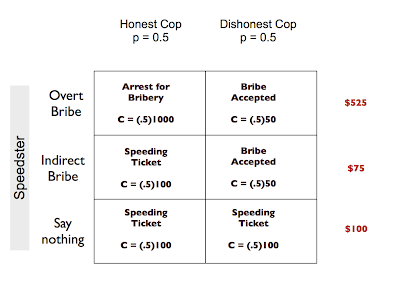

PNL argue that part of the answer to this question comes in the shape of plausible deniability. What indirect speech gives us, that direct speech cannot, is the ability to deny certain implications of our speech. This is useful in a variety of domains. In part one, we looked at the simple example of the police bribe, where denying that you are offering a bribe can be of great value. Similarly, in part two, we looked at the case of relationship negotiation, where plausible deniability allowed one to hover between different relationship types and thereby avoid giving offence.

This seems like a decent start to the explanation of indirect speech, but there is, however, a final puzzle that needs to be addressed. Why are there so many indirect speech acts whose implications cannot be plausibly denied? For example, expressions such as “would you like to come up and see my etchings?” or “this is a real nice place, it would be a shame if something happened to it” are indirect, but everyone knows what they really mean. The conventional implication is so widely understood that it seems odd that anyone would use them. So why do they stick around?

In the remainder of this post, we will look PNL’s solution to this puzzle. As we shall see, their argument is that even when the conventional implication of the phrase is widely understood, the phrase has some utility. To appreciate their argument, we need to do three things. First, we need to appreciate the digital nature of language. Second, we need to understand the concept of common knowledge. And third, we need to see how indirect speech blocks the route to common knowledge.

1. Language as a Digital Medium

PNL argue that language is tacitly perceived to be a digital medium. In using this term “digital” they mean to draw upon the digital/analog distinction. Roughly, a digital signal is one in which something has either one value or another, there is no intermediate state; whereas an analog signal is one that is continuously variable. The classic example here comes from musical recordings. In an analog recording, a signal is taken from a recording device and directly laid down on (say) magnetic tape in an continuously varying sine wave. In a digital recording, the signal is sampled and laid down in a discrete discontinuous wave.

PNL say that language consists entirely of discrete signals — morphemes, words and sentences — which are combined in order to communicate meaning. There is a reasonable amount of evidence underlying this, some of which is discussed in Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought. To give a quick example, phenomena that are continuous in the real world (e.g. space and time) are digitised by language (e.g. “a moment in time”), resulting in a communicated meaning that is discrete and discontinuous.

None of this is to say that there aren’t a huge variety of shades of meaning present in language. Anyone with a passing familiarity with interpretive practices knows this. It is, however, to say that words and sentences are typically perceived to have a discrete meaning. In other words, people typically believe you to be saying one thing or another, not both.

This has three consequences for indirect speech, according to PNL. They are:

Overt Propositions serve as Focal Points: A focal point is a location within a physical space that two rational agents, acting independently, can coordinate on. The concept comes from Schelling’s work on game theory. He gave the example of two agents who wish to meet each other in New York on a particular day, but have not agreed a time and place. He argued that Grand Central Station at 12 noon would be an obvious focal point. PNL claim that something similar is true of overt or direct propositions. They are focal points within semantic space and two rational agents can coordinate on their meaning, acting independently. Indirect propositions, on the other hand, are not focal points and thus cannot serve the same coordinative function, even when their implications are 99% certain.

Playing to an Audience: According to some psychological theories (e.g. Goffman’s) people are always playing to a hypothetical audience,, when they say or do things, even if they have a real audience. Thus, when I talk to you I am obviously trying to say something to you, but I might also be playing to a hypothetical audience of eavesdroppers. This has an interesting effect on my use of indirect speech acts. Although the implications of those speech acts might be very clear in the particular context of my conversation with you, they might not be clear to the hypothetical audience. Thus, I may continue to use them, even when their implications are certain, because I have that audience in mind.

Blocking the Route to Common Knowledge: Because language is typically perceived to mean one thing or another, an indirect speech act — which hovers between at least two interpretations — can block the route to common knowledge. This has an interesting psychological effect on how people interpret the indirect speech, even if they are sure what the implication actually is.

This final suggestion is of most interest to me and so I’ll spend the remainder of the post fleshing it out. But I can’t resist passing some comment on the first suggestion. While I like the idea that overt propositions serve as focal points, I wonder whether this really helps to resolve the problem we started with. After all, focal points are largely a matter of convention. Grand Central Station serves as a focal point only to people who share a common set of assumptions. Similarly, a focal point of this sort could change over time. Thus, if Grand Central Station were knocked, another location might become a focal point. If this is right, then why can’t focal points change within semantic space too? Why can’t an initially indirect proposition come to treated like an overt proposition. Indeed, I have hard time believing that this hasn’t already happened when it comes to allegedly indirect locutions like “would you like to come up and see my etchings?”

2. Blocking the Route to Common Knowledge

If we are going to understand the “blocking the route to common knowledge”-argument, we’ll first need to understand what common knowledge really is. This is a technical concept from the literature on game theory, which can be defined in the following manner:

Common Knowledge: A proposition P is common knowledge among a group of agents G, if everyone in G knows P, they all know that they know P, they all know that they all know that they know P, and so on ad infinitum.

An example would be the following. You and I are sitting at a desk opposite each other. I take a banana out of my pocket and place it on the desk, announcing the fact as I do so, knowing that you can see and hear me. In this instance, there is common knowledge that there is a banana on the desk. Why? Because you and I both know that there is a banana on the desk. I know that you know that there is a banana on the desk, and you know that I know that there is a banana on the desk. Furthermore, I know that you know that I know that there is a banana on the desk, and you know that I know that you know that there is a banana on the desk. (And so on ad infinitum).

If you are confused by the recursive phrases — “I know that you know that I know…” — in this example, you are not alone. It is a difficult concept to wrap your head around. One way to get a better grasp on it is to contrast common knowledge with the closely related, but importantly different, concept of “mutual knowledge”. This is perhaps best illustrated by an example. This one is taken from Ben Polak’s lectures on game theory, available from the Open Yale website (lecture 2 if you must know).

Suppose we have two people facing forwards, looking in the same direction, but not at each other. Suppose that a third person approaches these two people from behind and then places a pink hat on each of their heads. This third person then gets the two people to face each other. Is the fact that at least one person is wearing a pink hat common knowledge?

The answer is: no. If you look at the diagram above, and follow my reasoning, you can see that the conditions for common knowledge are not met here. Person X knows that person Y is wearing a pink hat; and person Y knows that person X is wearing a pink hat. But X doesn’t know that Y knows that X is wearing a pink hat, nor does Y know that X knows that Y is wearing a pink hat. This is because neither of them knows what kind of hat they are wearing.

This actually gives us everything we need to understand PNL’s argument about indirect speech. For it is the distinction between common and mutual knowledge that allows them to conclude that indirect speech blocks the route to common knowledge, even when its implications are virtually certain. To put it most succinctly they argue that indirect speech gives us mutual knowledge, but not common knowledge.

Take a scenario in which A says to B: “would you like to come up and see my etchings?”. We can assume that A knows what the implication of this really is, and we can also grant that B knows what the implication is. Thus, there is mutual knowledge of the implication. But there isn’t common knowledge of the implication. Why not? Because B doesn’t know that A knows what the implication is, and A doesn’t know that B knows what the implication is. This is true even if there is 99% certainty of the implication on both sides. The lingering uncertainty blocks the route to common knowledge. This wouldn’t be true in the case of a direct proposition. If A had said to be “would you like to come up and have sex?” there would be common knowledge that A had made a sexual advance.

I think this is a pretty interesting argument.

3. Conclusion

To sum up, in this series we’ve looked at PNL’s theory of indirect speech. According to PNL indirect speech is used — despite its inefficiency — because it provides the speaker with a valuable commodity: plausible deniability. This is true even if the indirect speech act has an implication which is widely understood.

In this post, we explored some of the reasons for this. The primary argument advanced by PNL is that because language is tacitly perceived to be a digital medium — i.e. a medium in which words digitise continuous properties, and a proposition has either one meaning or another — the value of indirect speech is maintained even where its implications are widely known. One of the main reasons for this is that the use of an indirect speech act blocks the route to common knowledge.